This is the fourth post in a series about the Environmental Inequality class I finished teaching in December. The first post shared the syllabus and class project, the second described how I’ve used the documentary Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek, and the third described the first of two field trips we took – a boat tour of the Anacostia River. This post describes our class research project, undertaken in collaboration with the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Empower DC, and ANC 6D commissioner Rhonda Hamilton. Here is the project overview from the course syllabus:

This semester we will work on a collaborative research project with the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Empower DC, and ANC commissioner Rhonda Hamilton from the neighborhood directly adjacent to Buzzard Point in Washington, D.C. Buzzard Point is an industrial neighborhood that is currently being redeveloped. It will be the site of the new DC United Soccer Stadium and many other new construction projects. Our work will involve conducting oral history interviews with residents living near Buzzard Point to document their family history in the neighborhood, relationship to the community and to the adjacent Anacostia River, and experiences with pollution and gentrification. We will host guest speakers as well as go on field trips and conduct off-campus research activities as part of this project. The Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum will then add the transcripts to their archives and create a booklet based on your interviews to distribute to research participants after the class ends. When the booklet is ready (early 2017), there will be an optional reception at the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum to which you will be invited. This effort is a pilot project to upon which I hope to build a longer-term research relationship with our off-campus partners.

After working with the various groups involved to plan the project, I scheduled a number of “Class Project Days” in my syllabus to move the project forward. Here’s what we used them for.

Preparatory assignment: Research Ethics and the Institutional Review Board

Howard University requires all research plans, including research conducted by students as part of their coursework, to be approved by the campus Institutional Review Board (IRB). This process is designed to protect “human subjects,” or people that are the target of academic research, from potential harm. Accordingly, the students’ first assignment was to complete the IRB’s two required online short-courses on research ethics. They then submitted their certification of passing grades, along with their resume, to me. See the assignment prompt here. I submitted their certifications and resumes along with the rest of the paperwork for the proposed study to the IRB early in the semester. This was stressful as there was no guarantee that the campus IRB would approve the project in time for us to start and finish our work within the limits of a single semester. It worked out in the end, but I would recommend others submit and complete the IRB paperwork in the semester or summer before the class whenever possible. Then at the beginning of the class in which the research will be conducted, merely do the necessary paperwork to add students to the project as extra research personnel. I recommend this process even if your university does not require IRB approval for research conducted by students as part of their coursework. Going through the IRB approval process is educational for the students, reinforces the importance of taking seriously their interactions with the public as researchers, and enables the faculty member or students to publish out of the research they conduct.

Preparatory assignment: Practice interview

After covering the fundamentals of oral history interviewing, students were assigned a practice interview. They divided into pairs and interviewed each other outside of class, using modified versions of the same questions we intended to use with our real interviews later. Students had to record the interviews, write short papers about the interview (its form and content), and turn both in. See the assignment prompt here. In class we then discussed what worked well and what they would have done differently in order to improve their interviewing skills. After they conducted the practice interviews with sample questions I gave them, we also had a class discussion about what other questions ought to be added before we conducted our “real” interviews and I edited the list accordingly.

Guest speakers

On two different class days, I hosted guest speakers from our collaborating organizations to come tell us about their work and describe what they hoped to get out of the class project. Kari Fulton, Empower DC’s environmental justice organizer, spoke on the same day the students did a reading on the concept of cumulative environmental impacts – or the way multiple pollution sources add up to a cumulative health burden that is poorly understood by science and poorly addressed by regulation. Katrina Lashley, the Urban Waterways project coordinator at the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, spoke to the students on the same day they read about oral history interviewing.

Field Trip

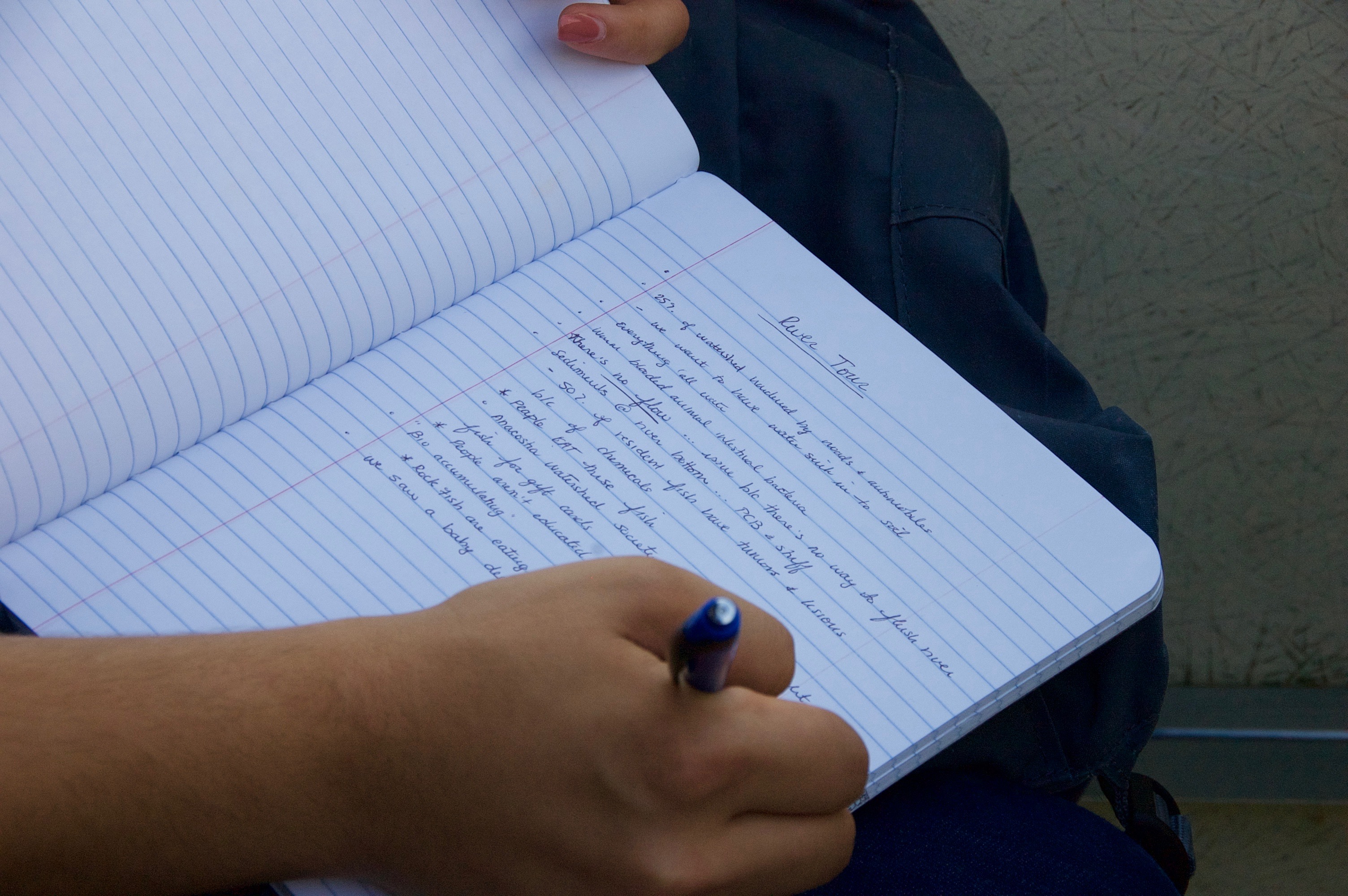

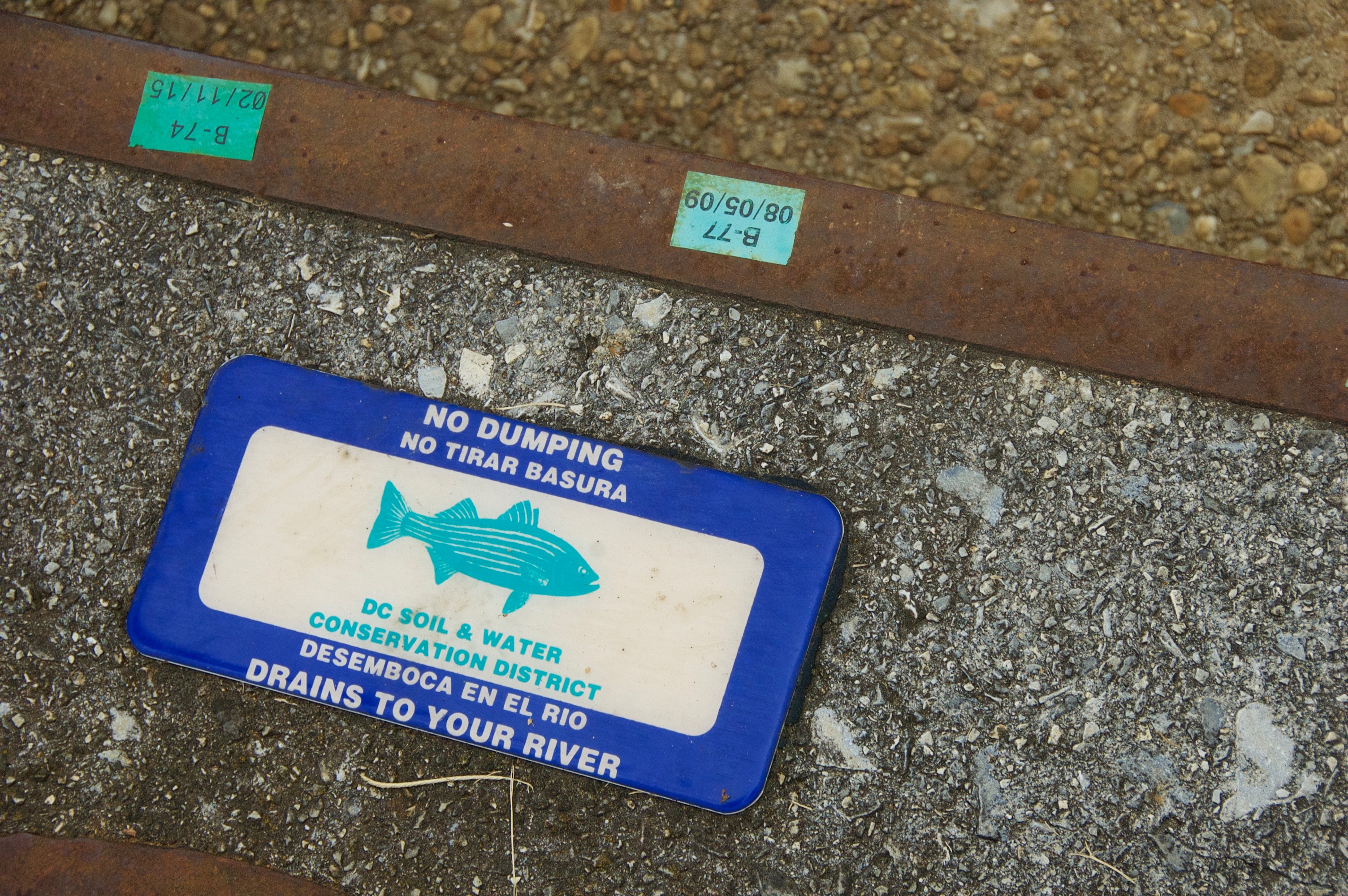

We also took a field-trip designed to help students better understand the local environment by taking a boat tour of the Anacostia River. See photos and a description here. Although many of the people living near Buzzard Point that we interviewed later in the semester had little contact with the nearby Anacostia and Potomac rivers, the field-trip still helped the students locate themselves and the project within Washington DC environmental concerns. If I teach this class again with the same research project, I hope to schedule a field-trip to the Buzzard Point neighborhood in place of, or in addition to, the river tour.

Readings

The topical readings of the course were relevant to the research we conducted. In addition, we read things designed to educate the students on the research process. These included the following:

- Hunt, Marjorie. 2012. Smithsonian Folklife and Oral History Interview Guide. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved August 21, 2016 (http://www.museumonmainstreet.org/education/Oral_History_Guide_Final.pdf)

- Cable, Sherry, Tamara Mix, and Donald Hastings. 2005. “Mission Impossible Environmental Justice Activists’ Collaborations with Professional Environmentalists and with Academics.” Pp. 55-75 in Power, Justice and the Environment: A Critical Appraisal of the Environmental Justice Movement, edited by D. Pellow, D. Naguib and R. J. Brulle. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

In addition, two other “Class Project Days” featured readings specific to our local research topic. One on the Anacostia River and was assigned the day before our river tour. The others included press coverage of the redevelopment efforts at Buzzard Point, neighborhood that was the target of our research. See the syllabus for details.

Outcome

By the time we got to conducting the actual interviews, the students were well prepared to do so professionally, though of course they still have room to improve their interviewing skills, as does any novice researcher. Our class traveled together to the Syphax Gardens public housing units to conduct the interviews after a meeting of the residents’ council. Some of the people there had been notified by our host, Rhonda Hamilton, that the interviews would be taking place, and others learned of our project for the first time that evening. Eight residents stayed after the meeting to be interviewed. The students individually reviewed the consent forms required by Howard and the Anacostia Museum with the residents before proceeding with the interviews. I floated through the two rooms in which the interviews were taking place to make myself available if any of the residents had questions the students could not answer.

In our next class, we discussed the following questions as a group to prompt the students to reflect on the interviewing experience and began to analyze the interviews themselves:

- What went well?

- What could be improved?

- What did you learn in your interview?

- What new questions did the interview leave you with?

After discussing these topics, I then linked the above questions to the methods, findings, and future research sections of the final papers that they would write. But before writing their final papers, the students had several other assignments. They wrote and sent thank-you notes to the people they interviewed, uploaded the audio files of the interviews to our course management system, and transcribed the interviews. Then they wrote final papers in which they analyzed not only their own interviews, but the interviews conducted by the entire group.

Overall, I’m pleased with how the project went. It was a good opportunity to learn more about ongoing environmental justice work in Washington D.C. for both myself and my students. The fact that many of the residents brought up similar issues that the students had read about during the course made everything more real to them. The students also seemed to enjoy the opportunity to take their learning outside of the university walls. For their part, the residents we interviewed seemed appreciative of the students’ interest and professionalism.

This semester, I continue to work on the project with one of my graduate student research assistants (Jesse Card), and one of the undergraduates from that class who has stayed on as a spring research assistant (Amanda Bonam). They did quality control on the student transcriptions by listening to the interview recordings and correcting the transcriptions as necessary, and then sending the corrected transcripts to the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum to place in their archives. Jesse is also sending copies of the transcripts and signed consent forms to all the participants. We are also conducting more interviews with other Syphax Gardens residents that were suggested during our first round of interviews. As a group, we will be reading through all the transcripts and recommending excerpts to feature in the booklet that the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum is making. My undergraduate research assistant is also communicating with the project partners about organizing a spring event to launch the booklet, and establishing a review process for the creation of the booklet. Between the three of us we have been attending ongoing public hearings about the development of Buzzard Point and its impact on neighboring residents. Amanda has adopted the project for her senior honors thesis, and Jesse will lead us in writing one or several academic articles out of the interview data, which parallels his own master’s thesis research. After this spring, we will revisit the project with all partners to discuss to potential of continuing or expanding it with my next batch of Environmental Inequality students in the fall.

See photos of our interview outing, and links to the class syllabus and assignment prompts ,below.

My students waiting for the residents’ council meeting to end and interviewing to begin.

Project partners Kari Fulton (Empower DC) and Rhonda Hamilton (ANC 6D).

Student Brittany Danzy interviews Ms. Mildred Young.

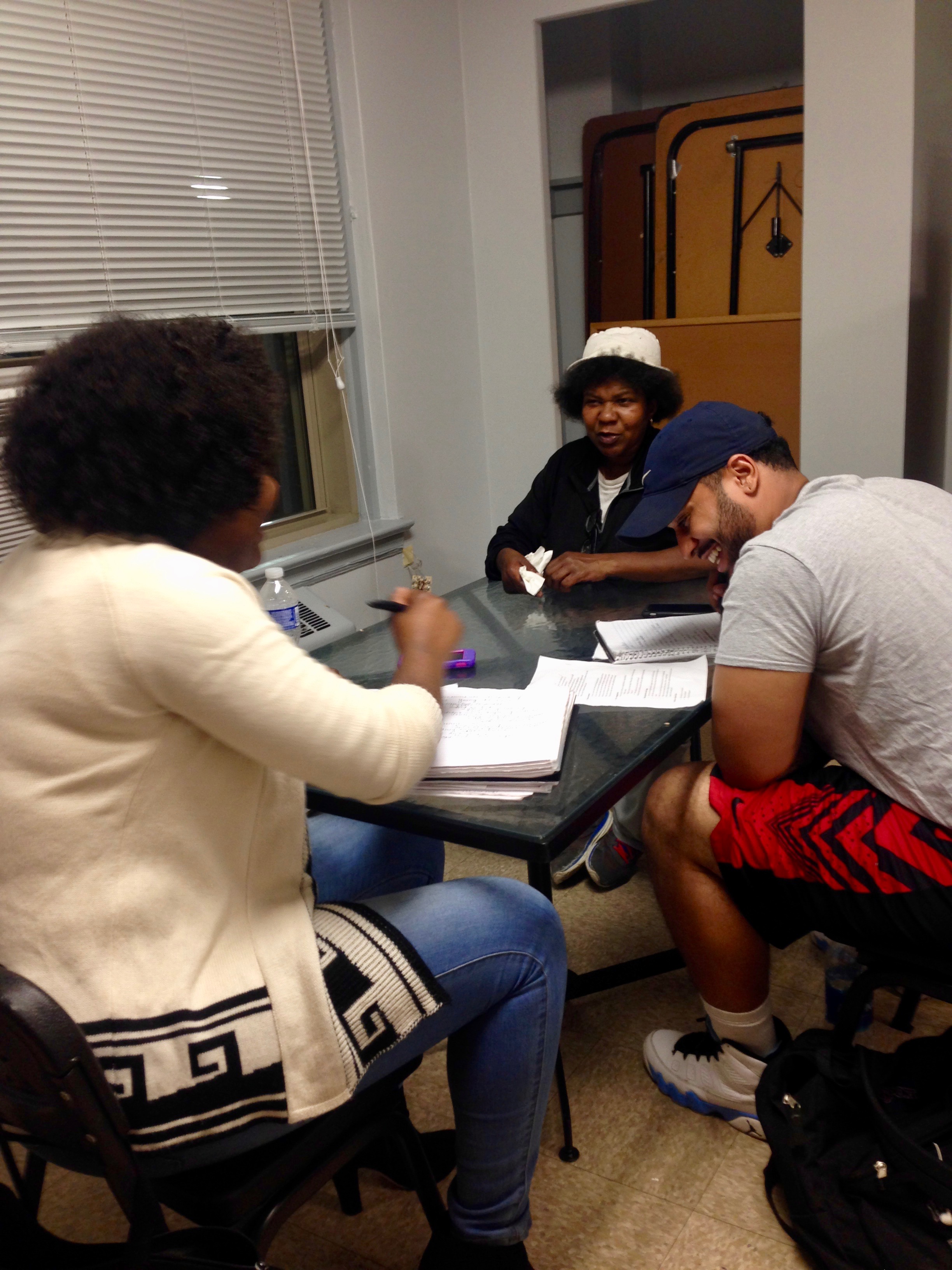

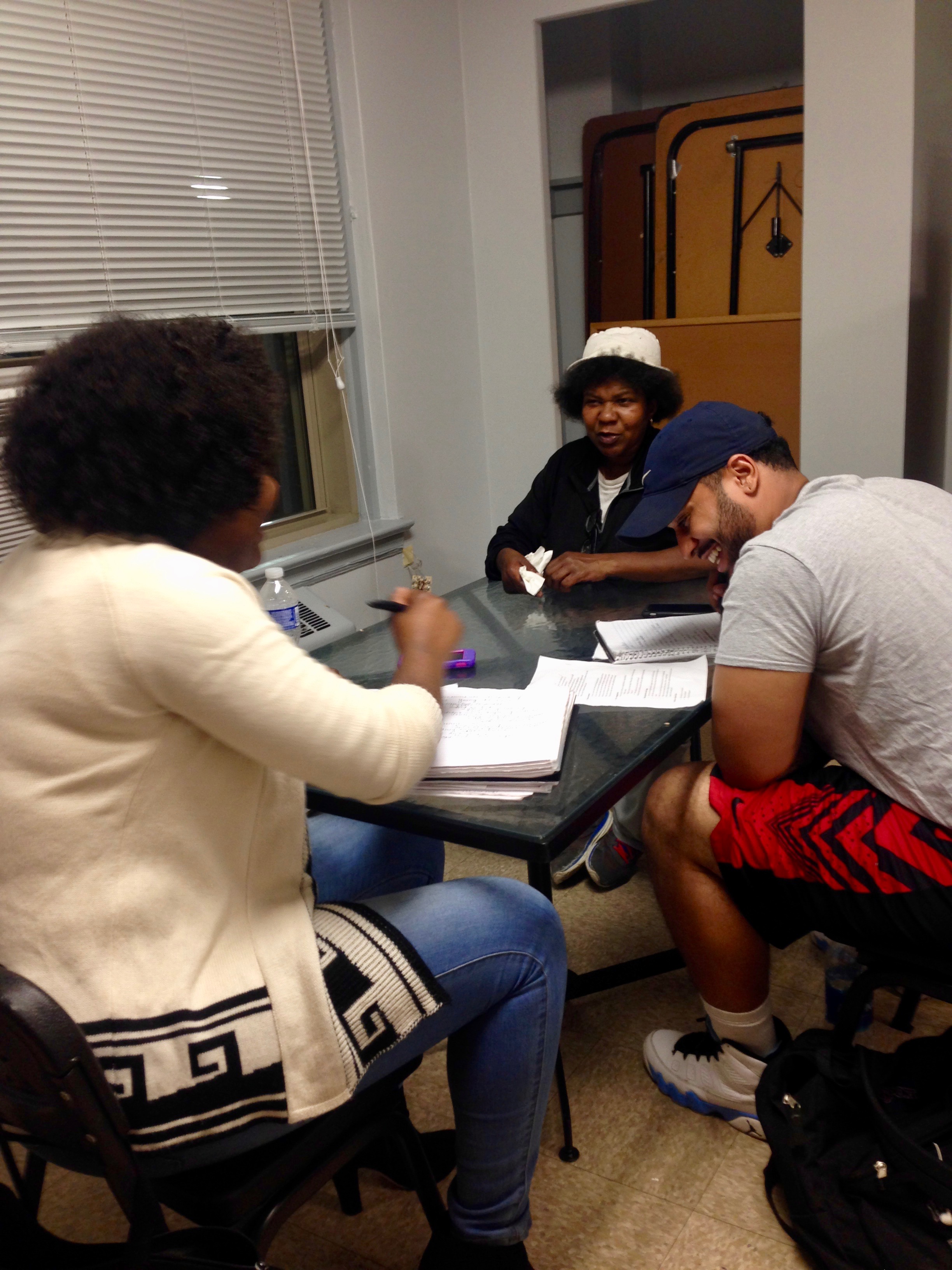

Students Tyla Swinton and Joseph Dillard are having a good time interviewing Ms. Michelle Young.

Students Ravelle Matthews and Romie Michel interview Ms. Mary Wilson.

Students Angelyna Seldon and Amanda Bonam interview Ms. Gloria Hamilton.

Kari Fulton’s son kept the students entertained when they weren’t otherwise occupied.

The view from Syphax Gardens public housing.

Class syllabus and assignment prompts: